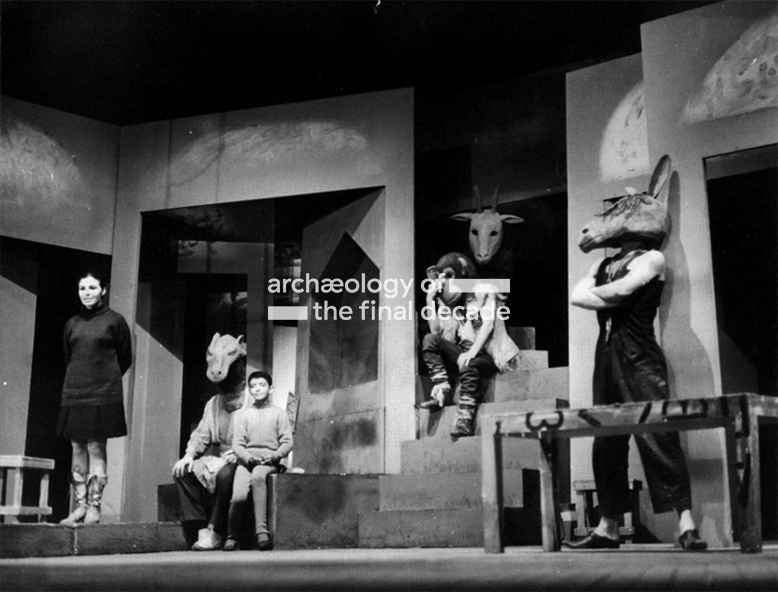

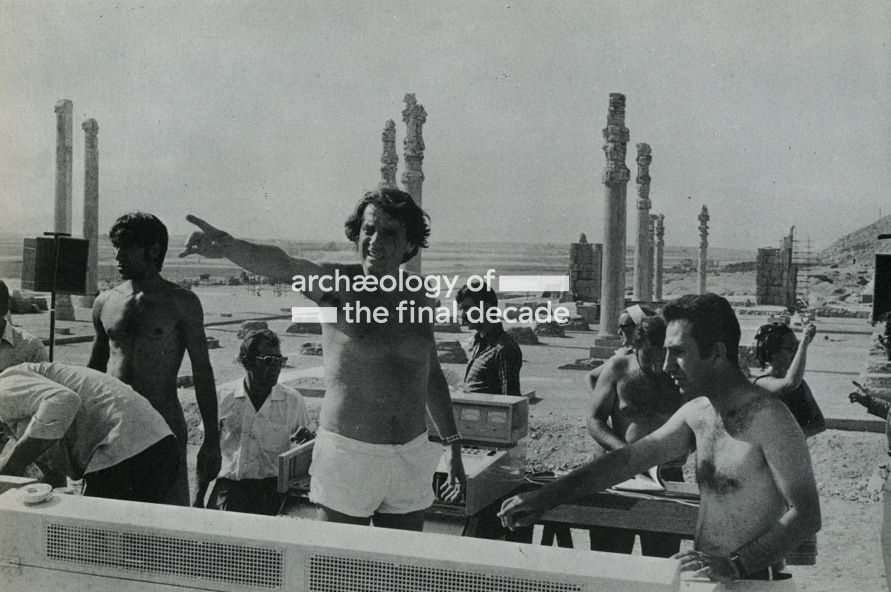

Festival of Arts, Shiraz-Persepolis is a virtually forgotten and radical international arts festival which took place in Iran between 1967-77. Archaeology of the Final Decade (AOTFD) excavates historical documentation to reveal a uniquely progressive crucible of intercultural collaboration, which was declared decadent and un-Islamic by fatwa in September 1977. All materials associated with the Festival were removed from public access after the Iranian Revolution in 1979, and these materials, as well as the festival itself, remain officially banned in Iran to this day.

The festival introduced artists and expressions from the Global South into international cultural discourse on an unprecedented scale, on an equal footing, radically dismantling the dominant hierarchies. After Iran, the most highly represented region was South Asia, re-invigorating strong but dormant cultural ties with countries like India, Bangladesh and Afghanistan which had been severed through colonial rule. In the immediate aftermath of decolonisation, Shiraz-Persepolis would shift the cultural centre of gravity towards the present and the re-emerging ‘other’ – consciously attempting to bypass the hierarchies and conventions of the European cultural terrain.

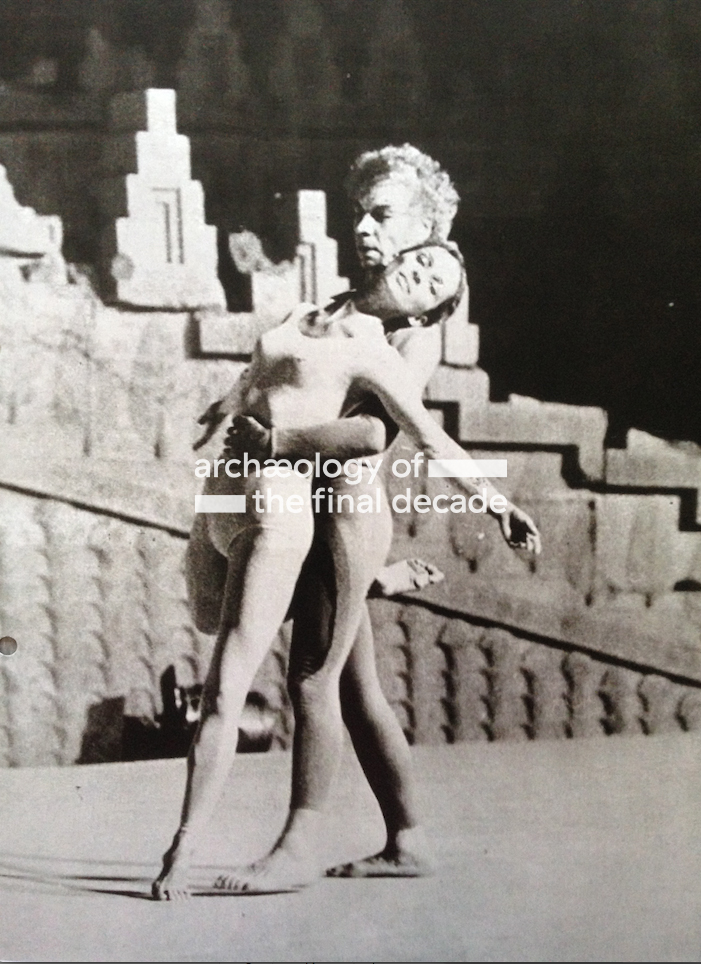

The local artistic scene shared a stage with the likes of Ravi Shankar, Yehudi Menuhin, Ram Narayan, Vilayat Khan, Rwandan percussionists, Japanese Noh, Balinese gamelan, and Indian kathakali performers, as well as creations, in many cases commissioned by the Festival, by Tadeusz Kantor, Jerzy Grotowski, Peter Brook, Shuji Terayama, Joseph Chaikin, Merce Cunningham, Robert Wilson, Maurice Béjart, John Cage, Gordon Mumma, Iannis Xenakis, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Robert Serumaga, and Núria Espert. Seminal experimental works were forged, at a time when most of the artists remained marginal in their own countries.

The potential fruits of this cultural tabula rasa were not only for local arts and culture, but would invite distant voices from Asia and Africa, to test their own received ideas on the nature of drama, music and performance against the backdrop of a new historical order, responding to the abrupt end of European domination.